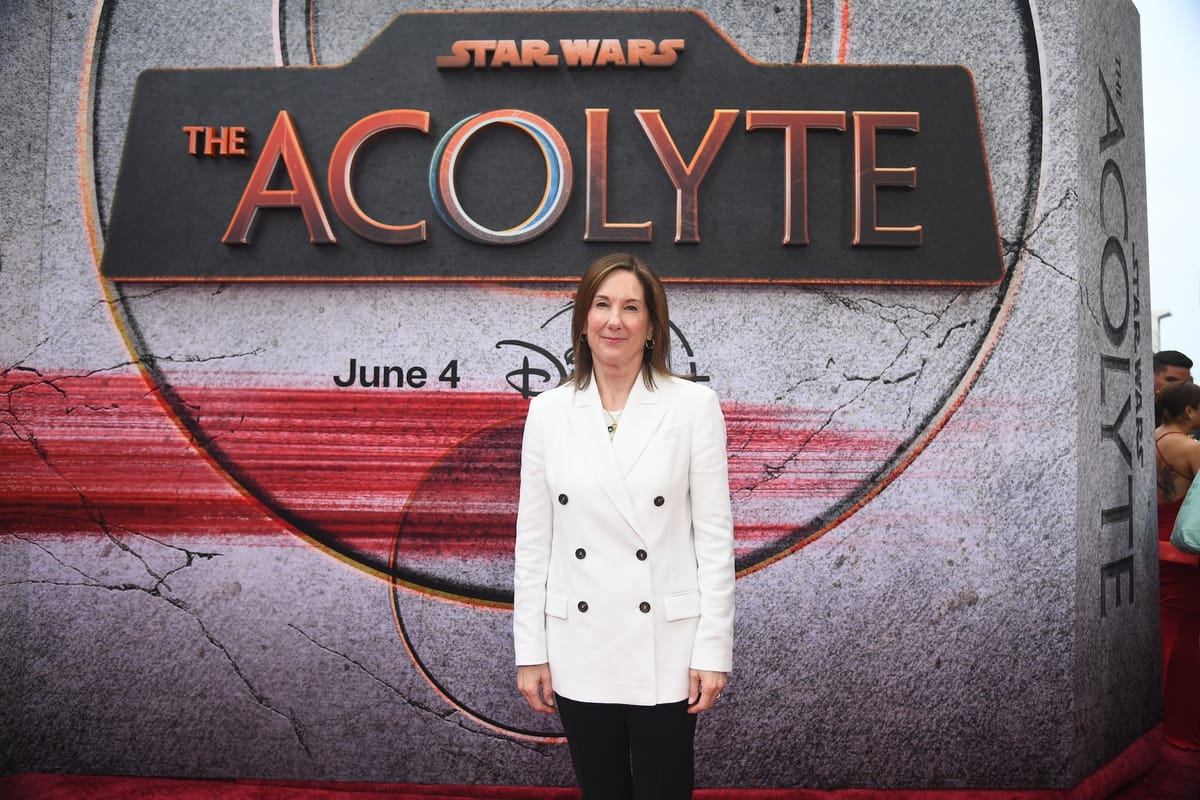

Kathleen Kennedy Wielded the Grey Side of The Force

Her leadership of Lucasfilm under Disney was a massive financial success. But creatively, ‘Star Wars’ feels more listless than ever before.

There’s a strange paradox at the core of Kathleen Kennedy’s leadership of Lucasfilm, which came to a close this week after fourteen years of leading the company once it was purchased by Disney back in 2012. On the one hand, you can point to Disney’s investment in Star Wars as a massive force (no pun intended) multiplier, removing the sore feelings from the Prequel Trilogy and re-energizing the franchise to be bigger than it ever had been before. There’s no question that Disney’s original $4 billion purchase for Lucasfilm has paid off many times over for the company, with the losses overshadowed through massive sales of not only movie tickets and Disney+ subscriptions but bottomless piles of merch and astounding theme park attendance. When you consider that Kennedy’s stewardship as President of the company went far beyond the latest movies and TV shows to encompass comics, attractions, video games, and more, she ensured that Disney would reap the rewards of their purchase.

And yet with a handful of exceptions, Kennedy also oversaw a Lucasfilm that played it safe at almost every step, to the point where their caution would hinder as much as it would help them. The Force Awakens was an incredibly safe movie (essentially repeating the beats of A New Hope with a few tweaks), but arguably a necessary one given the fallout of the prequels. But as the years wore on, Lucasfilm would leap to make splashy announcements about Star Wars things that didn’t happen, seemingly done to tease shareholders rather than move a film through production. Making movies is hard, but it seemed almost impossible to get them through Disney’s production pipeline with Star Wars being deemed so precious and fragile that a single false move could unravel that entire tapestry. Even movies that made it into production, like Rogue One and Solo, had to be massively retooled in order to satisfy Disney executives.

How do we square this circle? How did Star Wars become so creatively timid yet remain so popular? I’d boil it down to Disney shrugging off any interesting expansion of the Star Wars mythos in favor of courting heavy users. Disney has spent decades eschewing creative risks, running to the safety of franchises even when such a run made no sense (hello, Tron: Ares). To make something Star Wars, you couldn’t rock the boat too much, and risk was being determined by Disney executives, who are extremely paranoid (read any reporting on the Disney corporation and it sounds like a pit of vipers). For Kennedy to stay in power, her ultimate loyalty was to these forces, and weirdly, that removed her strongest asset coming into the job, which was as an effective producer.

A common saying among producers is that it’s their job to protect the director. What they mean by that is they’re the ones who have to absorb every logistical headache and put out every fire so that the director can focus on his or her creative vision. Together with her husband, Frank Marshall, Kennedy did that for decades for Steven Spielberg, and as much as Spielberg is a creative genius, I’m not sure he would have reached the zenith of Hollywood filmmaking without Marshall and Kennedy. And yet at Lucasfilm, Kennedy has rarely shown such advocacy for filmmakers. Within the corporate machine, the importance was on meeting release dates, and what was yesterday’s exciting pitch became today’s risky investment.

I can’t overlook how exciting the franchise could be under Kennedy’s watch. The Last Jedi is proof that the world of the Skywalker Saga could thrive beyond George Lucas’ vision and not within an imitation of what came before. There are glimmers of greatness in Rogue One, especially its third act. In its first two seasons, The Mandalorian was a breezy, enjoyable show. And Andor isn’t just great for a Star Wars TV show, but great for any TV show, period.

But these feel like outliers in the staid, corporate-approved vision of what Kennedy and Disney wanted Star Wars to be. They released a making-of documentary for The Force Awakens that neglects to mention that Harrison Ford broke his leg during production, despite that news being in every trade paper when it happened. They spiked the release of a JW Rinzler book on the film’s production, worried that letting people know about the tumult of making a hit movie might somehow diminish its standing. And the stories they sought to tell frequently demonstrated the cost of the studio’s caution.

How else to explain the misbegotten The Book of Boba Fett? The show tried to deepen the Boba Fett character only to run into the problem that because they didn’t want to risk making him The Mandalorian, they no longer had a place for the legacy character beyond, “Uh, mob boss? Anyway, here’s more Mandalorian and Grogu.” How do you untangle the bleak, heavy tone of Kenobi’s first episode, only for it to quickly rush into the safety of pairing Obi-Wan with a little Leia and another confrontation with Vader, as if these don’t create strange narrative wrinkles for A New Hope? Why did The Acolyte’s storytelling drag on so slowly (Sol has something very important to tell Osha or Mae—oops, interrupted) when it had so much room to play with unmapped portions of the Star Wars universe?

I do sympathize with the difficulty of appeasing corporate overlords and also trying to usher along interesting stories (not to mention the vast amounts of sexism and racism frequently emanating from the fandom’s worst and loudest voices). But the direction Kennedy picked is the one where Star Wars will continue: Dave Filoni’s insular, lore-focused nonsense that is ultimately only for die-hards. Filoni will take over as President (while remaining Chief Creative Officer) alongside Lynwen Brennan, the studio’s business affairs and operations chief. Filoni was the mind behind The Clone Wars TV series and has been a frequent contributor in steering the direction of Star Wars for years. Moving him to the Presidency should make for a smooth corporate transition, but it also signals that Disney sees no issue with his uninspiring creative decisions.

Filoni rarely seems interested in worthwhile dramatic stakes or pushing Star Wars towards anything that would challenge the fandom. Instead, his storytelling frequently reads like trying to retrofit anything unpopular in the mythos, like the prequels, and finding ways to make them appealing. If you devour every episode of anything Star Wars, I suppose there’s some payoff there. For the rest of us, we’re left to wonder why Darth Maul now has robotic spider legs or who the hell this guy is. Disney is making the bet that Star Wars can be like the Marvel Cinematic Universe, where every tease is meant to pull fans in deeper, so that if you’re confused, that’s only encouragement to delve further into the franchise for answers. However, that doesn’t even seem to be working out for Marvel anymore, and I’m not sure why such hidebound storytelling would be more appealing for Star Wars.

Kennedy’s legacy at Lucasfilm feels like a story of brand resuscitation without requiring particularly great storytelling or even cultural cache. The Mandalorian and Grogu arrives this May, and while it will be the first Star Wars movie since the abysmal The Rise of Skywalker, it also seems like right now, people are largely greeting the feature with a shrug. Perhaps that will change as the film gets closer, but it’s possible that casual moviegoers aren’t interested in a movie that carries three seasons of TV baggage with it (3.5 if you count Book of Boba Fett). But that’s what Star Wars does now: it churns out Star Wars stuff that never gets people riled up one way or the other. For Disney, any creative risk could cause people to have a strong opinion, and there’s the risk that all the positive opinions could get drowned out by the negative ones. For a world with a mystical force defined by a light side and a dark side, Kennedy leaves us a galaxy that looks grey and muted.