For Whom Do We Cheer?

The Netflix docuseries 'Cheer' raises interesting questions about what we look for in a leader.

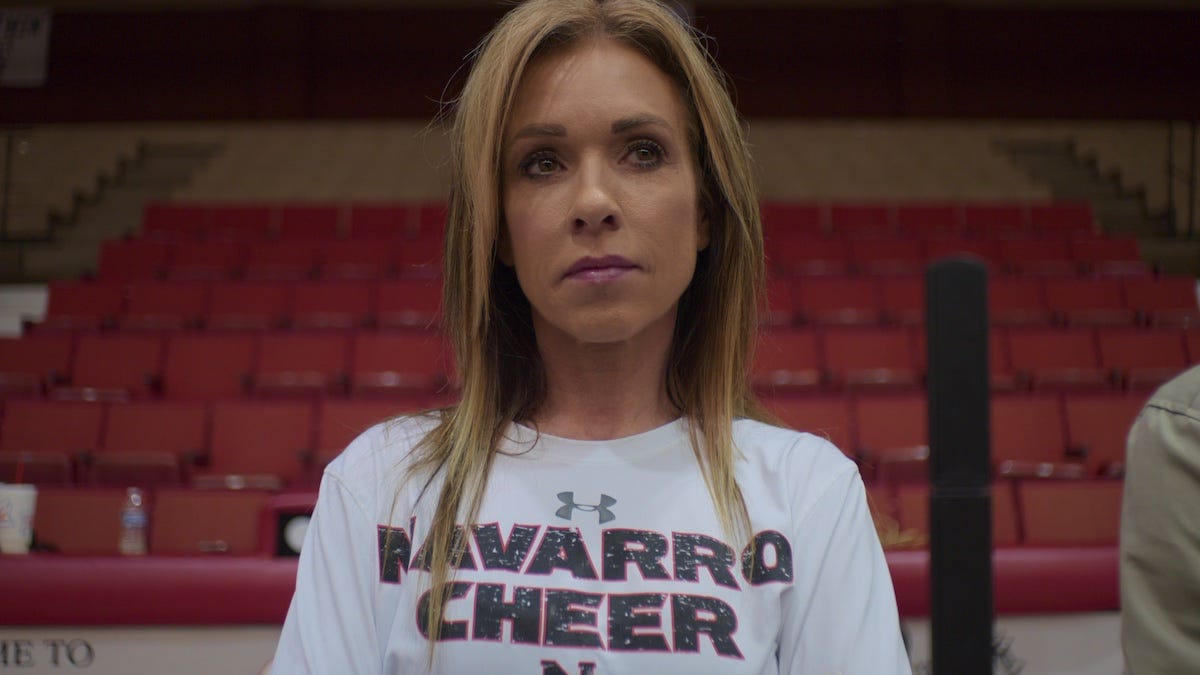

Thanks to my lovely wife, I recently caught up with the Netflix docuseries Cheer. I was under the assumption that it was a reality TV series about the lives of cheerleaders, but the show is far more serious-minded about the nature and commitment of sport, especially one that’s as physically demanding as cheerleading. The first season, which aired at the beginning of 2020, chronicles the Navarro College cheerleading squad led by coach Monica Aldama. Season One was a massive hit, and led to unexpected stardom for the documentary’s subjects. This led to a longer Season Two that looked at not only Navarro College but their main competition, Trinity Valley Community College. The story also expanded not only how fame had affected Aldama and members of the Navarro squad, but also the monstrous actions of former Navarro cheerleader Jerry Harris.

But I’m not really interested in Harris’ story. Clearly, his actions took everyone around him by surprise. They didn’t know there was a monster in their midst, and so it feels unreasonable that the filmmakers should have picked up on it either. The story about Jerry Harris is pretty straightforward: he seemed like a likable underdog, he was actually a sexual predator, and now he’s likely going to prison for quite some time. While his depiction raises questions on whether anyone should be shown in a favorable light, I think to assume that everyone is secretly a horrible person is not a great way to approach a documentary subject (or life in general).

The person that fascinates me is Aldama, and what her coaching says about what we expect from leaders, especially women in leadership roles.

“Nobody Knows Anybody. Not That Well.”

Before I continue, I feel it’s important to stress that when I talk about Aldama, I’m talking about her depiction in Cheer. I don’t know her personally or have even met her. While documentaries profess to show the truth, at the end of the day, it’s still in the hands of an author who’s constructing a portrait. That author, if they’re acting in good faith (as I believe those behind Cheer are doing), strives to show as complete a picture as possible. Nevertheless, they only have so much access and the show’s center is the relationship between Aldama and her athletes as opposed to Aldama and her friends or Aldama and her family.

I make this preface because I don’t want to be unfair to an individual who presumably went into the first season simply wanting to highlight her work and the work of her championship team. Yes, there are risks when opening yourself up to a camera crew and your show will be broadcast on a platform as large as Netflix (although no one knows what will catch on when it airs on Netflix), but I get why it was a mutually beneficial relationship for Aldama and the filmmakers. The filmmakers get the story of interesting cheerleaders on a team known for winning the national championship, and Navarro College gets to further establish itself as the destination for the nation’s best cheerleaders.

But then the show got popular, opinions started forming about Aldama, and it’s worth exploring what the depiction of Aldama means.

What Does It Mean to Be a Good Coach?

Aldama’s success is undeniable. You don’t win 14 championships over the course 20 seasons if you’re not exceptionally good at what it is you do. In the same way that people praise coaches like Nick Saban or Bill Belichick, Aldama has the same track record of consistency, and it’s worthwhile for a docuseries to take a closeup look at what exactly has led to that success.

Where Cheer gets tricky is in Aldama’s approach to coaching. Cheer shows that some of these athletes (or at least the ones they choose to feature) tend to come from troubled backgrounds where they felt they were lacking a parent figure. For these cheerleaders, Aldama represents a maternal presence. More than one athlete says that Aldama is like a mother or a second mother to them, and I’m sure that bond makes them want to compete harder.

The problem is that the relationship between athlete and coach can never be like one between a child and parent. That’s not to say that Aldama doesn’t care about her athletes, but also that what she wants from the relationship and what her athletes want are two different things. Ostensibly, they both want to win the championship, but Aldama’s primary goal is victory. Her success as a coach is measured by wins and losses. While athletes will come and go at Navarro, Aldama’s position is contingent on her ability to field a competitive team that has a serious shot at winning every year. If they don't win, then she’s objectively not doing a good job.

But the cheerleaders—or at least the ones featured—are looking for something different. They’re looking for a mother-figure, and that’s a problem because the way Cheer depicts Aldama, she’s playing on that affection while looking to utilize it for a championship. It makes the relationship between Aldama and her cheerleaders transactional. Aldama will play the mother figure, but you need to give everything you’ve got for her affection. If you’re not talented enough to make mat, then her attention is going to go elsewhere. It leads to an unbalanced situation where cheerleaders—who are about 18-21 years old—are looking for a mother’s love, but that love is conditional on the ability to succeed at cheerleading.

That means Aldama is working a psychological lever that feels unfair to her cheerleaders. That’s not to say that coaches can’t love their athletes, but again, you have to look at what each side wants out of the relationship. If Aldama wanted her cheerleaders to simply be the best people they could be, that would be a different outcome. There are coaches who aren’t in it for wins, or rather, they believe that helping people to become their best selves will lead to championships. But their main goal is personal enrichment rather than aiming for the championship. Aldama makes it clear that she’s in it for the championship, and again, that’s fine, but it forces young people into situation where their sense of self is now tied into a win/loss binary. If they don’t break themselves in practice, can they maintain Aldama’s affection and attention?

Coaches at a high level make high demands of their athletes, and Aldama is no different. As one talking head points out, Aldama is no different than a Saban or a Belichick who expects athletes to do their jobs and give 110%. You can argue that those methods are too harsh, and Aldama’s counterpart at Trinity, Vontae Johnson, seems like a fairly standard coach—shouting his disappointment, working his team relentlessly, and encouraging them when they do well. Aldama, on the other hand, seems to have an emotional lever at her disposal, which is where I get uncomfortable with her coaching style.

This of course leads to the question, “What is the correct coaching style?” If the only options are yelling at athletes or emotionally manipulating athletes, then the only way that’s left is maybe the Ted Lasso School of Coaching, which has the benefit of being fictional. The worst thing about sports is that it’s binary. Someone has to win and someone has to lose, and the best way to get a good performance out of someone is to tie their self-esteem to the outcome of a competition. It’s not particularly healthy, but that’s how the game is played.

The only way I see out of that is to pay athletes. Some may counter that the economics don’t work or that once you open the door to paying athletes you have to scale what each athlete gets paid based on their performance and so on and so forth, but here are the facts: athletes generate revenue for schools. Not all programs generate revenue equally, but they all exist because they benefit the school in some way. Some may argue that the scholarship is the payment, but there are kids who get scholarships who don’t have to risk concussions for the school. Watching Cheer, you can see how physically demanding this is, and it’s nice that these athletes love to cheerlead, but also their work has value as does the risk they incur with the damage to their bodies.

Perhaps I’m being unreasonable. Perhaps this world “works” in that the cheerleaders love Aldama, Aldama loves the cheerleaders, and everyone gives everything they have because they want to win so badly, and that desire to win pushes them to their limits. Maybe cheerleading is no different than college football and only the scale and popularity are different. But watching Cheer, I couldn’t help but feel that everything was a bit off. When a coach says she loves her athletes, it should be for who they are rather than for what they can win.