‘A House of Dynamite’ Is Too Self-Serious to Embrace Its Underlying Absurdity

Extreme competence will not save us.

Sidney Lumet’s 1964 Cold War thriller Fail Safe is a great movie. It depicts the crisis that emerges when a nuclear bomber is sent to Moscow, and the attempts to pull it back. And yet, as good as Lumet’s movie is, the one that stands as a towering classic is Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove: or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, which came out nine months earlier. Both movies use a similar plot, but whereas Lumet played the stakes for tense drama, Kubrick leaned into the underlying absurdity of handling world-ending weapons. A House of Dynamite tries to take the Fail Safe approach, demonstrating how much research screenwriter Noah Oppenheim did into what our response would be in the event of a nuclear attack. As much as director Kathryn Bigelow tries to wring maximum tension from every moment, the movie’s celebration of competence feels empty as the missile barrels towards a major U.S. city. It’s a movie that undermines its own drama, as what unfolds shows us how doomed we are before someone even launches the nuke.

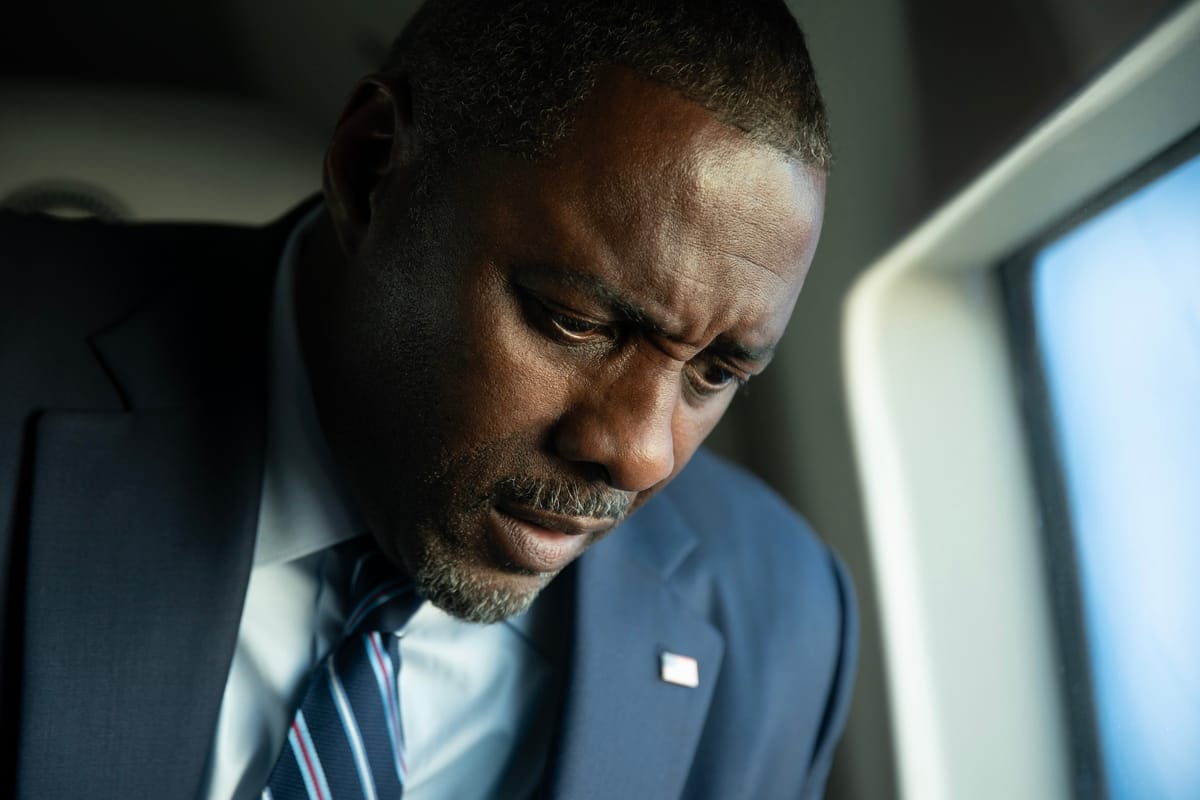

There’s an odd recursive structure to A House of Dynamite, where we start by following the people tasked with overseeing threats to the U.S. and then expanding the narrative to bring in more powerful players. Right before the missile hits, we then cut back and see the same events from a different perspective of people higher up the chain until the third act, when we’re sitting with the President (Idris Elba) as he wrestles with the decision of whether to counterattack. At every level, most people are simply trying their best, and the movie emphasizes that those tasked with preventing nuclear Armageddon are just normal citizens who are eating chips at their desk or eager to get home and see their kids. What’s meant to be horrifying is that, as much as these people race to stop the unthinkable from happening, there may be no system that can stop the “house” from exploding.

And yet…this seems pretty obvious? At best, A House of Dynamite feels like it speaks to an argument made by author and critic Will Leitch during the first Trump Administration, which is that we’ve forgotten how to fear. In his article, Leitch cites the haunting 1983 film Testament, in which life slowly starts coming to an end after a nuclear attack. It's a movie that speaks to a country still aware of how nuclear war would mean the slow death of all life on Earth. However, part of what gives that film its power is how far removed the characters are from the epicenter of the disaster. It’s not Fail Safe or even The Day After. It’s the encroaching decline that you’re powerless to stop. Bigelow seeks to replicate that powerlessness but struggles to find the emotional core since the whole endeavor feels more like a research paper than a story with real people. A House of Dynamite craves the immediacy of characters who know the bomb is coming, and yet their powerlessness is rendered as tragic inadequacy. They can have procedures in place, but their countermeasures are shockingly weak. “A coin toss! That’s what $50 billion buys us?” the Secretary of Defense (Jared Harris) moans when learning about the defense system that's meant to knock an incoming nuclear weapon off course.

However, rather than the comedy of shocked indignation, A House of Dynamite is more in line with the mournful note sounded by a soldier who says, “We did everything right!” Strangely, the film can never reconcile just how foolhardy this system is when doing everything right nets you the same outcome as doing everything wrong. We’re meant to be horrified by how much expertise is required for these situations and how little those in power know about nuclear warfare, but through this rendering, it doesn’t really matter. The game has been played before the nuke even launches, which, for all the film’s structural dancing, leaves us right back to where we started before the story even began—even one nuclear weapon is one nuclear weapon too many.

That means A House of Dynamite has little to offer beyond the plainly evident and the intensity that Bigelow can bring to bear on the story. The film is sprinkled with the core absurdities of our nuclear world, but they linger at the outskirts as if this is no laughing matter. But what exactly are we supposed to do? The film never explores why countries have clung to their nuclear arms in the first place, and if we’re pretty much screwed if even one random nuke comes hurdling towards us, then what’s left? We’ve shown our commitment to electing fundamentally unserious people to positions of great power, and even if we valued expertise like we should, A House of Dynamite argues that it’s still far too little to counteract the underlying threat.

The thudding dramatic weight of the film unravels as it keeps circling back only to arrive at the same idea that even the most well-intentioned and competent people can be impotent in the face of nuclear arms. Bigelow and Oppenheim aim to shock and horrify us, but I left the film feeling oddly relieved. Our current government is filled with some of the most unfit goons imaginable, but if even the best people can’t turn back the Doomsday Clock, then I suppose I shouldn’t sweat it. I won't ever love the bomb, but A House of Dynamite, despite its clear intentions to fry my nerves and stress me out, got me to stop worrying.

A House of Dynamite opens in theaters today in limited release. The film arrives on Netflix on October 24th.