‘Nouvelle Vague’ Is a Love Letter to Cinema. It’s Weird That It’s on Netflix.

Richard Linklater’s latest will send you hunting for New Wave movies that aren’t available on the biggest streamer.

Nouvelle Vague is a big, unabashed love letter to New Wave cinema. Although the story is about the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, Richard Linklater’s movie has plenty of affection to go around for the filmmakers of the era, including Bresson, Rossellini, Melville, Truffaut, and more. It’s also a movie that jibes nicely with Linklater’s sensibilities, blending his love of place with spontaneous connection and how groups of like-minded individuals discuss their passions and ideals. What makes far less sense is why, after premiering at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival, Nouvelle Vague would land at Netflix other than “Netflix has money.” While it makes sense for the producers to recoup their investment, a movie about film as art will now live out its existence on a platform that sees film as content.

The story follows the ambitious and frustrated Jean-Luc Godard (Guillaume Marbeck), who feels like he’s being left behind by his peers from the Cahiers du Cinema—film critics who became groundbreaking directors. Eager to take his shot, he uses an outline from his pal and fellow filmmaker François Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard), and a small budget from producer Georges de Beauregard (Bruno Dreyfürst) to make what would become Breathless, one of the most important movies in cinema history. However, the production of the film baffles and frustrates almost everyone involved as Godard insists on finding the most natural, realistic way to capture his story. While it doesn’t seem to bother his freewheeling male lead, Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin), it certainly irritates Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch), a Hollywood actor unaccustomed to such a freewheeling affair. And yet even in these tense moments, there’s dancing, frivolity, and joy with an unwavering Godard driving towards his singular vision.

Although the making of Breathless pushes the plot forward, the film’s importance is taken as a given, and Linklater isn’t interested in educating those who are unfamiliar with the cinematic landmark. Nor is he eager to give a history lesson on how New Wave cinema developed across multiple countries and provided a distinctly different form of expression than what people had seen out of Hollywood. Instead, Linklater is in the same mode as Dazed and Confused or even his debut Slacker—people chatting, hanging out, and finding curious connections and conflicts. The intersection of people from different walks of life is a recurring theme in Linklater’s work, and it fits nicely into Nouvelle Vague, which marvels that so many talented artists were all in the same place at the same time. You may not know every single name that comes across the screen, but in Linklater’s eyes, they’re all valuable because they contributed to the transformation of cinema. We know the name “Jean-Luc Godard,” but we should also know Suzon Faye (Pauline Belle), the script supervisor, and Pierre Rissient (Benjamin Clery), the assistant director. In the world of Nouvelle Vague, when it comes to the making and appreciation of film, no one is unimportant.

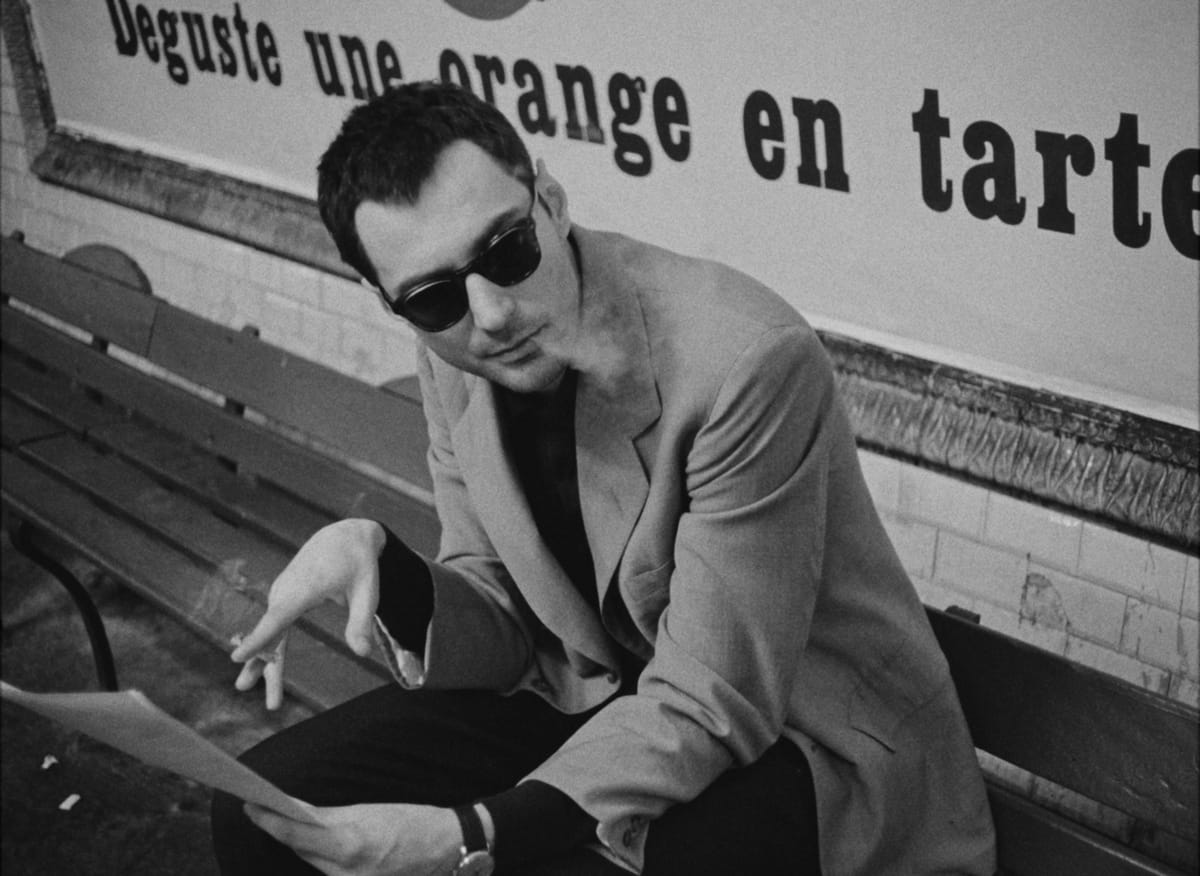

There are times where this love letter hits its limitations as Linklater almost resists the drama of a director on his first movie. Godard is unflappable, wearing his sunglasses everywhere (even at night or at the movies), and it’s a curious thing to depict a guy in his 20s who’s on the verge of changing movies forever, and he’s completely self-assured. On the one hand, that assurance does come through in Breathless, a movie that feels like the work of a far more seasoned filmmaker, but part of that film’s appeal (and arguably the appeal of similar New Wave movies) is how they rarely seek to explain motivations or desires. They’re more about an attitude, and while Linklater does his best to emulate that freewheeling approach, there are times when explaining why Breathless is the way that it is siphons the energy from Nouvelle Vague.

Thankfully, Linklater mostly succeeds in sharing his love of New Wave and the people who made it. The film relishes seeing a movie in a theater (one filled with cigarette smoke because 1950s France) and then discussing it afterwards with friends. It’s not just film as a vibe, but film as a practice, and what the world gained because these people not only made movies but also interacted with other moviemakers. As Godard chats up Roberto Rossellini or Jean-Pierre Melville, a viewer might wonder where they can see movies from these giants of cinema. The answer: not on Netflix.