‘Orwell: 2+2=5’: That’s Totalitarianism, Alright

Raoul Peck’s documentary uses Orwell’s writings to explain totalitarianism but does little to expand or unpack the famous author’s observations.

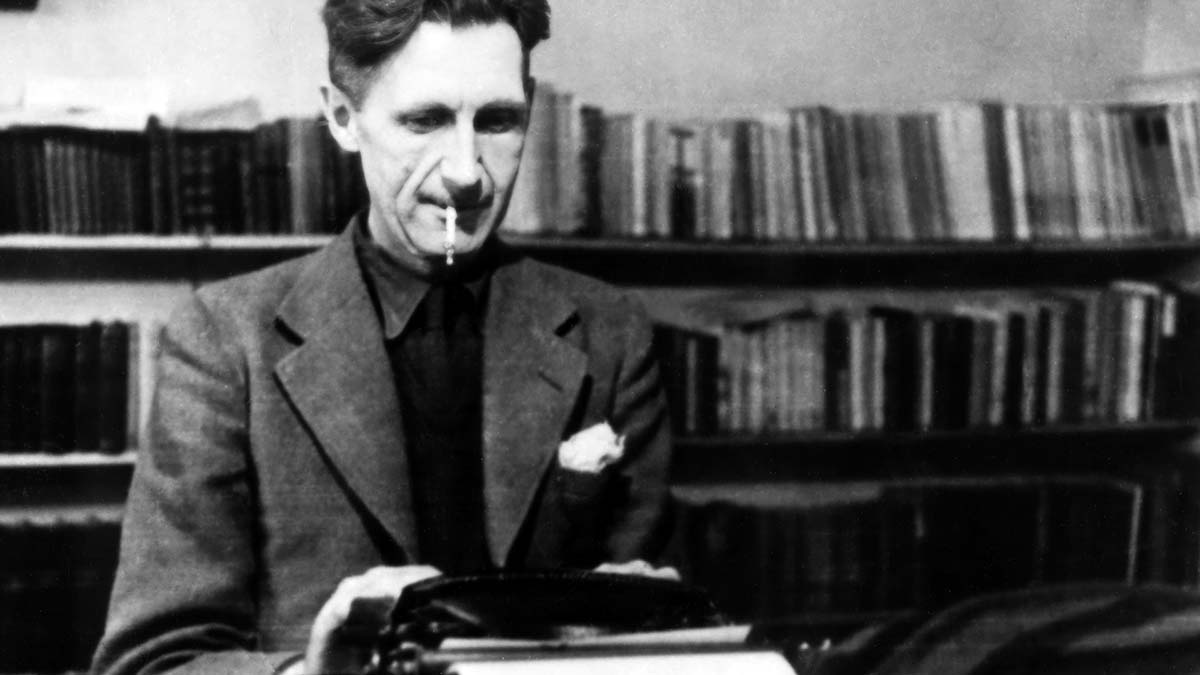

Now is not a bad time for a movie about the works of George Orwell. Authoritarianism is on the rise in the U.S. and abroad, and it’s important to understand how these movements coalesce and become part of daily life. We’re not outright living 1984, but there are enough similarities to be chilling. If Orwell was insightful enough to see far beyond his death in 1950 and into the decades to come, can those insights aid us in any way? Raoul Peck’s new documentary Orwell: 2+2=5 uses the author’s writing, both his fiction and his essays, to illuminate what we see today in our media, technology, and politics. Unfortunately, Peck never delves any deeper and stretches Orwell’s understandings to their very limits, at times even contradicting them to suit the shape of the movie. What begins as an energetic examination of Orwell’s life and work becomes as familiar and well-trod as noting a surveillance camera is “Big Brother.”

Peck weaves together three narrative threads in Orwell. The first are the major biographical beats of Orwell’s life told from the author’s perspective. The second comes as he works on 1984 while slowly dying from tuberculosis. The third comes from using Orwell’s essays and novels to illustrate the rise of totalitarianism across the 20th century and into the 21st century. Understanding Orwell’s upbringing in a classicist, colonialist society of pre-World War II England and then following him through places where there were always clear lines of oppressed and oppressors (at least in how he viewed the world, whether it was at Eton or in India) explains what informed his writing, and his desire to speak honestly when those in power would prefer to twist reality as a means of subjugating the powerless.

In its first half, Peck weaves these threads together well, painting a vivid picture of Orwell and what drove him to pursue not just writing essays and novels, but why the pursuit of truth in the face of authoritarian power was the driving theme of his work. Through Orwell’s writings (as read by Damian Lewis), we understand Orwell as not an outsider to the government’s cruelty, but someone who was both subject to those cruelties as well as a perpetrator of its injustices in India. Furthermore, these writings take on more power as Peck weaves in footage not just from the various film adaptations of 1984, but also newsreels and photos of authoritarian brutality across the 20th and 21st centuries.

And yet even as Peck uses the “three truths” of 1984’s ruling party as a way of structuring Orwell’s observations about totalitarianism (“Ignorance is Strength”, “Freedom Is Slavery”, “War Is Peace”), you can feel that Peck’s motivation is to scrape every current event and ill into Orwell’s forethought. For example, while Peck isn’t necessarily wrong that the rise of A.I. is a way of illustrating how “ignorance is strength” when social media tools disseminate falsehoods at astonishing speed, this is not an observation pioneered by or unique to Orwell, as much as his critique coincides with a certain societal ill. This recurrence across various issues aims to make Orwell an oracle of sorts whose observations, popular but unheeded, continue to reverberate because of humanity’s self-destructive patterns.

As the film drags on, you can feel Peck’s observations losing steam, and that he has made Orwell too big an umbrella for everything that’s happening without adding much in the way of texture or nuance. Part of this is how Orwell’s didacticism, morally correct but politically shaky (for example, if you reject all politics, as the film argues that Orwell does, then what upholds the freedom of the press, of which Orwell was a member?), can’t shine a fresh light on what’s already been well explored and loses necessary specificity to his themes. People know Orwell even if they’ve never read his books, but this can lead some to purposefully misread him. They look at any state action they dislike and call it “Big Brother.” Compare that to Peck’s terrific 2016 documentary I Am Not Your Negro, which is far more precise both in looking at James Baldwin and the effects of racial injustice.

I understand that Peck wants the audience to understand totalitarianism as Orwell understood it, but the breadth of the argument undermines the depth that could stick with the audience. The movie’s imagery of totalitarian action and actors raises questions the film doesn’t appear interested in pursuing, like “If Orwell’s political awakening came during his time as a member of a colonial power, then do totalitarianism's origins go back to imperialism? Where is the political cutoff? And if this is a 20th-century phenomenon, how does the colonialism of England differ from the fascism of the Third Reich? Through this lens, is totalitarianism merely a spectrum rather than a political philosophy?” I understand wanting to let Orwell speak in his own words, but at some point, you might need a political philosopher or a scholar to help take viewers to the next level rather than showing more clips of Donald Trump or Narendra Modi.

When Orwell reached its conclusion, I wished Peck had stayed true to the author’s fatalism. Orwell didn’t try to offer hope, and if anything, he actively rejects it, seeing the state and its actions as too powerful to counteract. And yet Peck egregiously flips the narrative of 1984. Winston’s observations about the proles are not meant to be prescriptive, but ironic. There are masses of people who could topple the party, but the proles are too uninterested and myopic to understand the larger political issues at play. That’s why the book doesn’t end with an uprising but with Winston so thoroughly hollowed out that his will has been replaced with party doctrine. That may not be the conclusion Peck wants to give his viewers, but if Orwell stands for unpleasant truths in the face of pleasant fictions, then the director should follow that belief to its bitter end rather than force a happy ending.

Peck tries to have it both ways, using Orwell’s tuberculosis as a symbol for dying democracies. We see the illness attack its host, and we hear labored breathing. This is meant to be totalitarianism attacking our institutions, but for Orwell, the battle had already been fought and lost. He could only observe its past and present, and while Peck may see a system on life support, the rendering presented in Orwell: 2+2=5 is a patient already in hospice. The body politic has been eaten away by authoritarian forces on all fronts—governmental, economic, and social—and I’m not sure if anyone can come away with a better understanding of the world than Orwell had in his final days. Peck may want his movie to be prescriptive, but his diagnosis is far more dire than any minor uplift he seeks to provide.

Orwell: 2+2=5 is now playing in select theaters.